This post looks at the strictness of spiritual Masters and the discipline needed to follow a lifelong spiritual life.

***

I grew up in Yorkshire and when I went down south to Oxford University – for comedic purposes – I would often exaggerate about how tough and grim life was up north. So it’s not surprising that one of my favourite comedy sketches is Monty Python and the Four Yorkshireman.

***

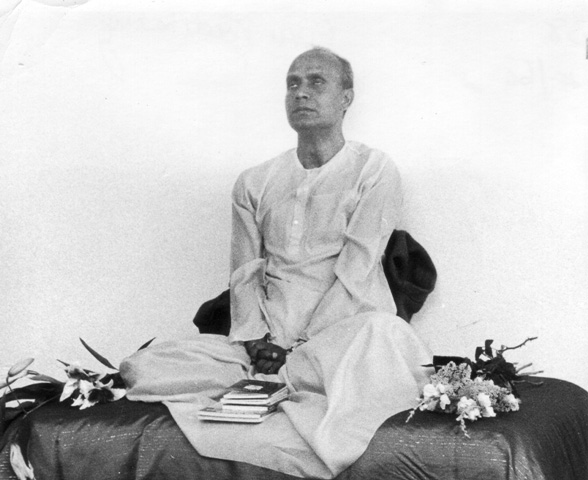

When I joined the Sri Chinmoy Centre, I would love to hear stories about disciples visiting Sri Chinmoy in New York. The stories were inspiring but also sounded quite intense – getting up at 6am to meditate, then running, then more meditation – then activities and more meditations until the early hours of the morning.

Then you would hear an older disciple say: “well you should have been around in the 1970s – we used to have to get up at 3am to get a bus in from Manhattan, for a 5am meditation, 10 mile run, and that was all before breakfast…”

And so it would go on, each disciple explaining in greater detail the tremendous intensity and great spiritual focus of life in New York. Though when I went to New York in 2000, I found a very relaxed atmosphere to complement the meditations. The disciples never mentioned how much time they spent eating and going to coffee shops.

Anyway, whatever stories of all night meditations and early morning marathons, it is hard to beat the discipline and intensity of some of the really strict Indian spiritual Masters, such as Devadas Maharaj, Swami Yutkeswar, and of course the famous yogi Milarepa.

At the same time, when we read about these genuine spiritual Masters, we feel the outer strictness is a complement to the inner love and concern. It is this real love and concern, which is behind the efforts to guide, mould and shape the aspiring human seeker.

On one occasion, Sri Chinmoy was asking a few disciples if they could stay on a Christmas Trip (spiritual vacation in Bali at five star hotel) for another week. This was Sri Chinmoy’s simple request, but it is the kind of request we might find hard to fulfil. At the time, we think of our work responsibilities and it can become hard to prioritise the spiritual life. In seeking the eternal, it is tempting to think we have eternal time. We want realisation, but we feel it can always put it off to a later date.

On paper, it is easy to prioritise spirituality, but in practise it can be more difficult. In Sri Chinmoy’s lifetime, I missed out on a few opportunities to travel and see my Guru and his unique Peace Concerts – opportunities I will never have again. My economist mind would weigh up the pros and cons, costs and benefits, and often took the conservative approach and didn’t go to as much as I could. Now these golden opportunities are no more.

Even now, having the determination to prioritise the spiritual life in simple ways requires a deep commitment and determination. I appreciate any seeker who can follow a spiritual discipline year in year out.

By contrast to our own fumbling attempts at obedience and discipline, through the ages you can hear some remarkable stories of devotion and obedience from the really great seekers and yogis. These stories are worth cherishing because they can remind me us of the benefits and beauty of a dogged determination.

Milarepa’s determination

In Milarepa’s case, his Guru told him to build a house. Milarepa was surprised because he hoped that he would be learning advanced meditation techniques – not manual labour. But, feeling obedience to his Guru was the highest ideal, he did build the house as instructed. On completing the house, far from praising his disciple, his Guru said that the house was not satisfactory – he must knock it down and start again. Milarepa did this – he knocked it down and built it to the new specifications. But on nine occasions, his Guru said it wasn’t good enough and he had to rebuild the house. It was only Milarepa’s burning aspiration and desire to realise the highest that kept him obeying his Guru’s seemingly tough outer commands and outer indifference.

In Milarepa’s case, his Guru told him to build a house. Milarepa was surprised because he hoped that he would be learning advanced meditation techniques – not manual labour. But, feeling obedience to his Guru was the highest ideal, he did build the house as instructed. On completing the house, far from praising his disciple, his Guru said that the house was not satisfactory – he must knock it down and start again. Milarepa did this – he knocked it down and built it to the new specifications. But on nine occasions, his Guru said it wasn’t good enough and he had to rebuild the house. It was only Milarepa’s burning aspiration and desire to realise the highest that kept him obeying his Guru’s seemingly tough outer commands and outer indifference.

Eventually, after many years of hard toil, Milarepa burnt off his bad karma and was rewarded with realisation; he became a famous yogi known throughout Tibet, and later the world. But, ten years of building houses and knocking them down certainly puts spending money on an air ticket to Prague into perspective.

Of course, spiritual Masters have to deal with seekers of different capacities. To one seeker, a daily ten minute meditation may be tremendous progress and real effort. To another seeker, the Master may see they have the capacity to meditate from 5am in the morning. A real Master will always care for the highest potential of his disciple – and this may well involve challenging them to go out of their comfort zone. A Master is also concerned in keeping his disciples balanced. It is sometimes the ego, which likes to choose the hardest path, but suffering is no guarantee of progress. A seeker of the calibre of Milarepa is rare indeed!

Following is a story by Sri Chinmoy about the spiritual Master, Devadas Maharaj and his disciple Ramdas. Ramdas had tremendous potential and capacity, but the story is instructive for showing how a real spiritual Master is willing to show tough love in order to get the best from his disciple.

When I think about the difficulty of getting up at 6am to meditate after seven hours sleep, I shall think of this story.

****

This is my last warning

When Ramdas was a young boy, one night he and his Guru, Devadas Maharaj, were meditating separately at different places. It was snowing heavily and the weather was extremely cold. Each one had an open fire in front of him to keep him warm. Ramdas meditated a few hours; then he fell asleep. When he woke up, he saw that the fire was totally extinguished. He was frightened to death, for he knew that his Master would be furious if he went to him to get a few burning coals. But at the same time he was unable to bear the cold weather. Finally he mustered courage and went to his Master for a few burning charcoals.

Devadas Maharaj came out of his trance and insulted Ramdas mercilessly. “Who asked you to leave your parents and your family if sleep is so important in your life?” he shouted. “This is my last warning. If you ever fall asleep again when you are supposed to be meditating, I shall not keep you as my disciple. You do not deserve to be my disciple.”

India and her miracle-feast: come and enjoy yourself, part 5 Traditional Indian stories about Devadas Maharaj, Agni Press, 1977 at Sri Chinmoy Library

< /hr>

I should add: Ramdas Kathiya Baba went on to become a great spiritual Master in his own right.

In Milarepa’s case, his Guru told him to build a house. Milarepa was surprised because he hoped that he would be learning advanced meditation techniques – not manual labour. But, feeling obedience to his Guru was the highest ideal, he did build the house as instructed. On completing the house, far from praising his disciple, his Guru said that the house was not satisfactory – he must knock it down and start again. Milarepa did this – he knocked it down and built it to the new specifications. But on nine occasions, his Guru said it wasn’t good enough and he had to rebuild the house. It was only Milarepa’s burning aspiration and desire to realise the highest that kept him obeying his Guru’s seemingly tough outer commands and outer indifference.

In Milarepa’s case, his Guru told him to build a house. Milarepa was surprised because he hoped that he would be learning advanced meditation techniques – not manual labour. But, feeling obedience to his Guru was the highest ideal, he did build the house as instructed. On completing the house, far from praising his disciple, his Guru said that the house was not satisfactory – he must knock it down and start again. Milarepa did this – he knocked it down and built it to the new specifications. But on nine occasions, his Guru said it wasn’t good enough and he had to rebuild the house. It was only Milarepa’s burning aspiration and desire to realise the highest that kept him obeying his Guru’s seemingly tough outer commands and outer indifference.