In one of his travel diaries, Oku no Hosomichi, the 17th century Japanese Haiku poet Bashō most famously wrote, “A lifetime adrift in a boat or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.” Born in 1644, near Ueno, in Iga Province, about thirty miles southeast of Kyoto, Bashō’s first poem was published in 1662. Over the next decade his poems continued to be published in various anthologies. In the spring of 1672 he moved to Edo to further his study of poetry. He undertook arduous studies in Chinese and Japanese literature, philosophy, and history. His studies also included Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and Shintoism. By 1680 he made a name for himself as a poet and taught poetry to quite a few students. Basho is considered one of the most learned poets of his time. In spite of his success as a poet, Bashō was lonely and dissatisfied. From 1682 Basho started undertaking long journeys on foot. On each journey he maintained a dairy which turned out to be a new poetic form he created called haibun. In haibun, Basho combined haiku and prose to trace his journey. This combination of prose and poetry was rich in two kinds of images: the external images observed on the journey and the internal images that these outer images invoked in the mind of the poet. Starting from 1684 Basho composed several such travel diaries that included Nozarashi Kiko, or Travelogue of Weather-Beaten Bones (1685); Oi no Kobumi, or The Knapsack Notebook (1688); and Sarashina Kiko, or Sarashina Travelogue (1688).

It was his last travel diary, Oku no Hosomichi, or The Narrow Road to the Deep North, that turned out to be his best and most famous piece of literary work. Basho composed this poetic travel journal on the last long foot journey that he undertook to the northern provinces of Honshu, covering 1,200 miles in over five months. He started his journey in the beginning of May 1689 and was accompanied by his student Kawai Sora. Their goal was to visit Oku that lay north of Sendai by following a narrow path that passed through the Sirakawa barrier, over the mountains. Both of them headed north to Hiraizumi, which they reached in one and half months. They then walked to the western side of the island, touring Kisakata and began hiking back along the coastline returning to Edo in late 1691.

When Basho was about to start on his journey many friends come to see him off. He describes this touching scene by putting into words an internal image that passes through his mind, “I felt three thousand miles rushing through my heart, the whole world only a dream. I saw it through farewell tears.” (1) Then he goes on to pen the following haiku:

Spring passes

And the birds cry out-tears

In the eyes of fishes

In this haiku, Basho is trying to convey the depth of his sorrow at parting with his close friends. The sorrow was so great that even the birds were crying and he increases the intensity by saying there were even tears in the eyes of fishes.

Many of the places visited by them had a lot of cultural and spiritual history behind them. These were places that were described by other poets of the past and Basho refers to these poems in his writing. For instance when he reached a beach called Shiogama, it was evening. After the summer rain the sky was just clearing revealing a pale moon over Magaki Island. This beautiful twilight scene reminded Basho of a line from Kokinshu’s poem, “fishing boats pulling together” and for the first time he understood what the poet meant.

Along the Michinoku

Everyplace is wonderful,

But in Shiogama

Fishing boats pulling together

Are most amazing of all.

On this journey into the deep north, often his mind soared into the rich depths of the Japanese history, culture and Zen philosophy. From those aesthetic heights, Basho came out with insights that are golden nuggets of human thought. The form was in prose but on reading the aftertaste is sheer poetry. When visiting a shrine at dawn, he gives the following description, “huge, stately pillars, bright painted rafters, and a long stone walkway rising steeply under a morning sun that danced and flashed along the red lacquered fence. I thought, “As long as the road is, even if it ends in dust, the gods come with us, keeping a watchful eye. This is our culture’s greatest gift.” (2). For a moment it is worth pondering on Basho’s insight. This shrine was five centuries old at the time of Basho. It seems what Basho is trying to tell us is that far into the future, maybe hundreds of years later, if a devout pilgrim visits this shrine and even if the shrine is in complete ruins, the pilgrim will receive the blessings of the gods he has come to pay homage to. The shrine which is something physical is time-bound (i.e.bound to decay with time) but its essence “the blessings of the gods” is timeless, eternal.

During their journey, Basho and his companion decided to spend a night at a place called Iizuka in a country inn. As it was a country inn the facilities were less than basic. After they had gone to bed, there was a heavy rain storm. Basho writes, “Suddenly a thunderous downpour and leaky roof aroused us, fleas and mosquitoes everywhere. Old infirmities tortured me through the long, sleepless night.”(3) At another time when for days and days they had to walk through rain and heat Basho wrote, “Through nine hellish days of heat and rain, all my old maladies tormenting me again, feverish and weak, I could not write.”(4) Sometimes for days they also had to walk through marsh land. These and other descriptions give one the impression that the journey was arduous and physically very difficult as Basho was of a delicate constitution and suffered from several chronic diseases. Also travelling by foot in seventeenth-century medieval Japan was immensely dangerous and hazardous. Yet Basho was willing to risk his life for the rich experience of his journey. In fact he considered it a pilgrimage.

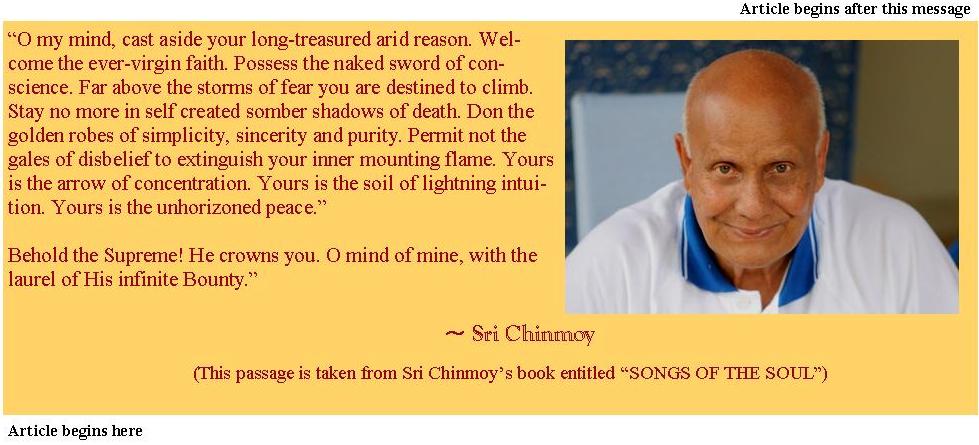

By the time Basho composed his last diary, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, he had matured as a poet. The Narrow Road to the Deep North was the climax in his literary career. Using his close interaction with nature as a tool, Basho was always trying to be in resonance with something within him that was impersonal, deep and meaningful. Once when he was passing through a remote forest area where a few hermits lived in thatched huts under pine trees, Basho wrote, “Smoke of burning leaves and pine cones drew me on, touching something deep inside.” (5) Sri Chinmoy said, “Art in the most effective sense of the term is a sublime truth that draws our soul from within towards the infinite vast.” Through his poetry, Basho tried to achieve this artistic excellence. His poetry was based on the Zen concept that one attains perfect spiritual serenity by immersing oneself in the egoless, impersonal life of nature. The complete absorption of one’s petty ego into the vast, powerful, magnificent universe. Hamill writes, “When he (Basho) invokes the call of a cuckoo, invokes its lonely cry. Things are as they are. Insight permits him to perceive a natural poignancy in the beauty of temporal things – mono_no_aware – and cultivate its expression into great art.”(pg. xiv)

References

1. Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho, trans, Sam Hamill, Shambhala, Pg. 4

2. Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho, trans, Sam Hamill, Shambhala, Pg. 16

3. Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho, trans, Sam Hamill, Shambhala, Pg. 12

4. Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho, trans, Sam Hamill, Shambhala, Pg. 28

5. Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho, trans, Sam Hamill, Shambhala, Pg. 17

6. Narrow Road to the Interior, Basho, trans, Sam Hamill, Shambhala, Pg. xiv